Almost a decade after the case of the priest Fernando Karadima broke the taboo in Chile and spurred the denunciation of abuses in countries such as Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua, or Argentina, the victims complain that the enormous power that the Catholic Church retains has achieved consolidate the cover-up, dilute the media and social pressure and slow down the judicial process.

An intimidating political and social influence that is reflected in the figures: despite being the region of the planet with the largest Catholic population and the scene of some of the most famous cases, Latin America also stands out for being the one with the lowest rate of complaints -barely a thousand-, according to UN statistics.

And although in 2019 the prestigious British think tank Child Rights International Network (CRIN) predicted a reactivation thanks to the involvement of organizations such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which in December 2020 announced a defense program for victims.

The truth is that since then the controversy has almost disappeared from the media and legal focus due, according to some experts, to the Covid-19 pandemic but above all to the effective action of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, which has redoubled a strategy based on the concealment, the fear of unleashing family conflicts, shame, and different social stigmas towards homosexuality, a prejudice that is still widespread throughout the continent.

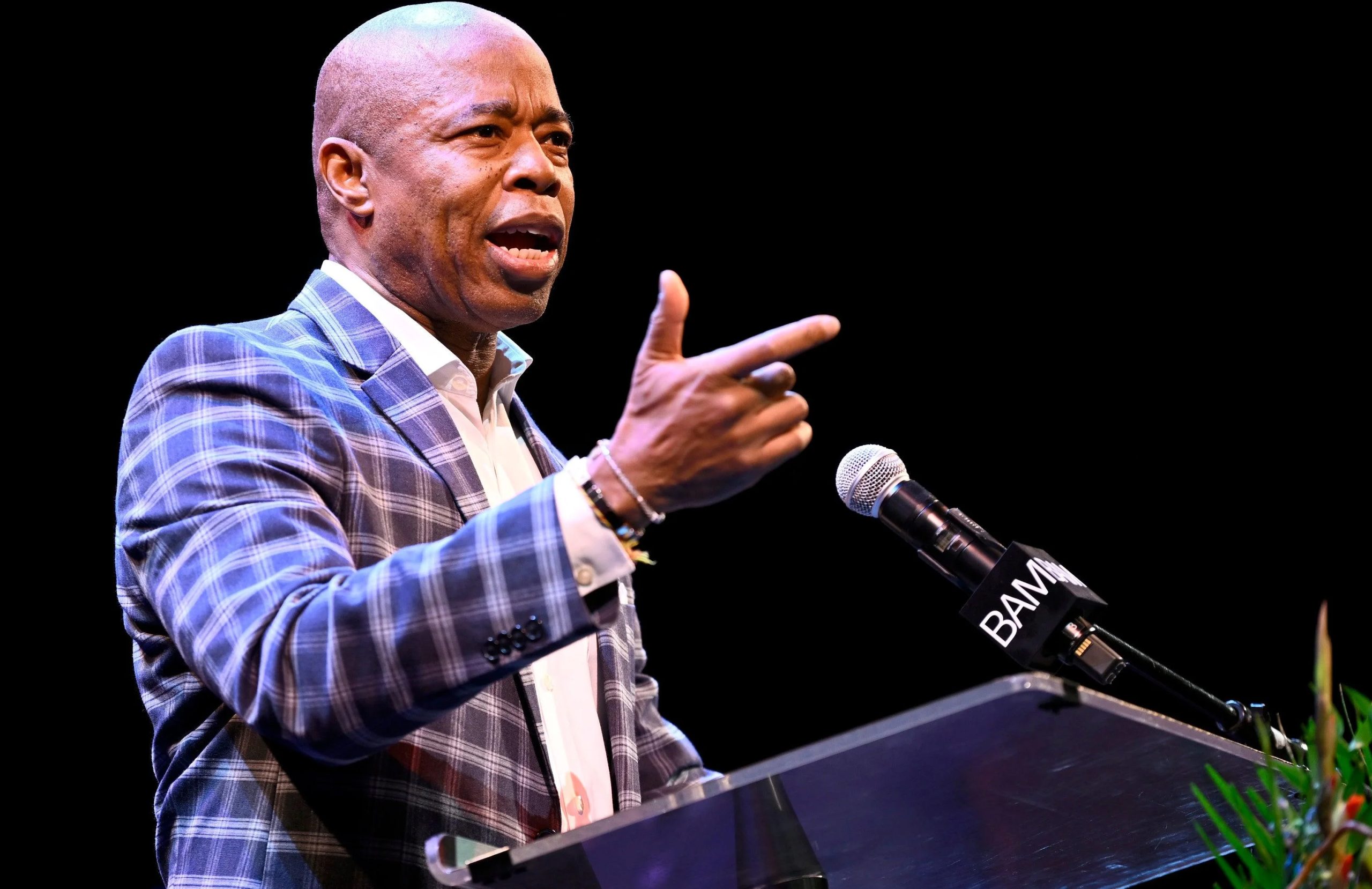

“The truth is that even the Prosecutor’s Office has lowered the intensity of the persecution a lot, which is curious,” explains Chilean José Andrés Murillo, a victim of the late priest Karadima, whom the Vatican condemned in 2011 for abuses committed between 1980 and 2006, and who died without being accountable to civil justice.

“In order to face (the problem) in a real and sustainable way, it is necessary to go to the root. And that is what they have not done in the Church, go to the root of the power structure, the structure of abuse, what is the that has caused the abuse to occur and what has caused the cover-up to occur,” he adds.

“Speaking of Chile, probably in absolute terms we did not experience the worst, but it did have a much higher level of publicity because today people are more aware. But in Bolivia, in Paraguay, in Mexico, in Brazil, in El Salvador, the power that the Catholic Church has is really hallucinogenic and very dangerous,” he warns.

COVER-UP AND IGNORANCE IN COLOMBIA

Cover-up, collusion, and ecclesial power are the terms that victims and investigators also highlight in Colombia, despite the fact that the Catholic Church recognized in 2019 more than a hundred cases committed by priests.

“In the Archdiocese of Medellin alone there are at least 43 religious with a history of sexual abuse of minors,” explains journalist Juan Pablo Barrientos, author of the book “Let the children come closer to me,” in which the case of Father Roberto Cadavid, “a sexual predator who raped children in a parish in Bello.”

Cadavid had to be taken out of this municipality of Antioquia by the Police “when the combos (gangs dedicated to drug trafficking and extortion) were going to kill him precisely because he raped the little brother of one of the criminals,” he recalls.

But far from punishing him, he was transferred in 2005 to another parish where he continued to accumulate complaints, so many that the Archbishop of Medellín, Monsignor Ricardo Tobón Restrepo, chose to send him to New York to try to cover up the scandal.

“Here we see a case of covering up and protecting a pedophile that has been documented for four years,” argues Barrientos, for whom only the tip of a pyramid is known, which in his opinion has a very broad base.

“In Medellin, there are not one or two or three, but there are dozens of pedophile priests. I think the number could exceed 100 priests who have abused children and adolescents and who are still in parishes, protected by the archbishop of Medellin. I could say that between 20 and 30% of priests (in Colombia) have complaints of sexual abuse of children and adolescents, “he says.

“GOD IN HEAVEN AND MARCO DESSI ON EARTH”

In Nicaragua, the case of Marco Dessi, an Italian priest tried and convicted in Italy for abusing six minors in the Chinandega province, where he lived for 30 years, shows how that ecclesial power is projected through an almost mystical veneration, which acts as a protective shield, especially among the poorer classes.

There, many of the complaints did not prosper due to the attacks launched against the first six complainants, who were criticized for vilifying a holy man who had founded the Hogar del Niño, the Getsemaní Community, a children’s choir, and many other works for the benefit of Chinandegan children and adolescents, their victims, explains Lorna Norori Gutiérrez, coordinator of the Movement Against Sexual Abuse.

There was an “impressive devotion” to Dessi, who was supported with vigils, rosaries, processions, and even pronouncements by Nicaraguan personalities. The pressure caused four to stay abroad, and only two returned to Nicaragua, where they live without talking about it and with a low profile.

“We can say that we will never know how many children and adolescents were abused by Dessi”, who found thousands of photos and videos of child pornography on his computer, warns Gutiérrez for whom Dessi took advantage, it is not known if consciously, of affection, trust and devotion.

“I visited the families of these children and adolescents, poor families from Chinandega, who totally trusted the priest, assumed that their children could not be safer anywhere else than with their father. In Chinandega they say: God in heaven and the priest Marco Dessi on earth”, says the researcher, for whom this power has meant that other complaints have not prospered.

According to their records, the first case was that of the priest, Zenón Corrales, in charge of a parish in the city of Matagalpa (north), accused of abusing a girl in 1997. The answer was to transfer him to another parish. After the Dessi scandal, complaints multiplied in the cities of Granada, Diriomo, Bluefields, Camoapa, Masaya, and Juigalpa but the pattern was repeated: the Nicaraguan Catholic hierarchy responded with the transfer as a way to cover up the crime, he insists.

ABUSES IN THE COUNTRY OF POPE FRANCIS

For years, the Argentine Church has tried to avoid allegations of sexual abuse of minors, opting for the strictest silence.

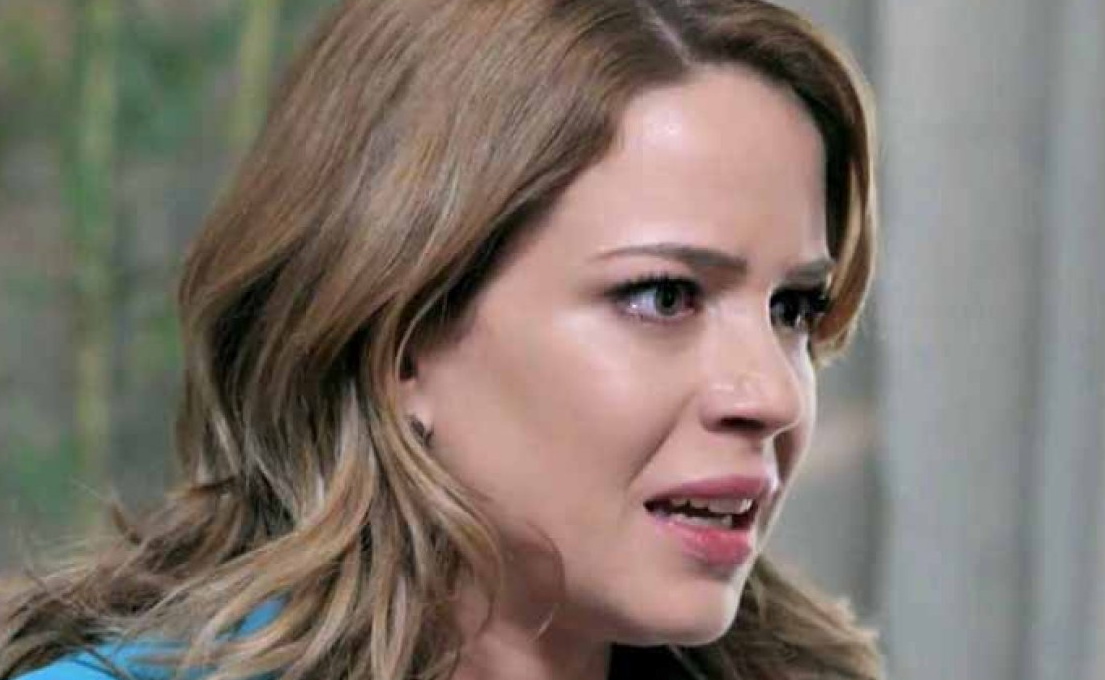

An example of this concealment policy is Sebastián Cuattromo, who suffered abuse at the Colegio Marianista de Buenos Aires, an institution “strongly authoritarian, where there were multiple cases of abuse of power.”

“That boy that I was when I was thirteen years old felt very vulnerable at school, in front of this sexual abuser who was the Marianist brother Fernando Picciochi,” Cuattromo relates. After twelve years of fighting in the courts, in 2012, the Argentine Justice sentenced the abuser to twelve years in prison, a “reparatory” experience for the abused but which revealed the “institutional culture of abuse of power, violence, and mistreatment”.

Ten years earlier, in 2002, the school had offered Cuattromo civil compensation for the damages caused, as long as he kept it in the strictest confidence. What did Cuattromo do then? Go to the Archbishopric of Buenos Aires, led by then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, current Pope Francis, to find out if the Church endorsed the attempts to hide this reality.

After several meetings with Bishop Mario Poli, the Church informed Cuattromo that it supported the school’s attitude, highlighting the “underestimating” treatment of the highest ecclesiastical authorities.

“Those deep, radical policy changes that should be produced in the Catholic Church with respect to complicity with the aggressors, the cover-ups, the ignorance of the pain of the victims, are very far from having occurred,” says Cuattromo.

NO PUNISHMENT

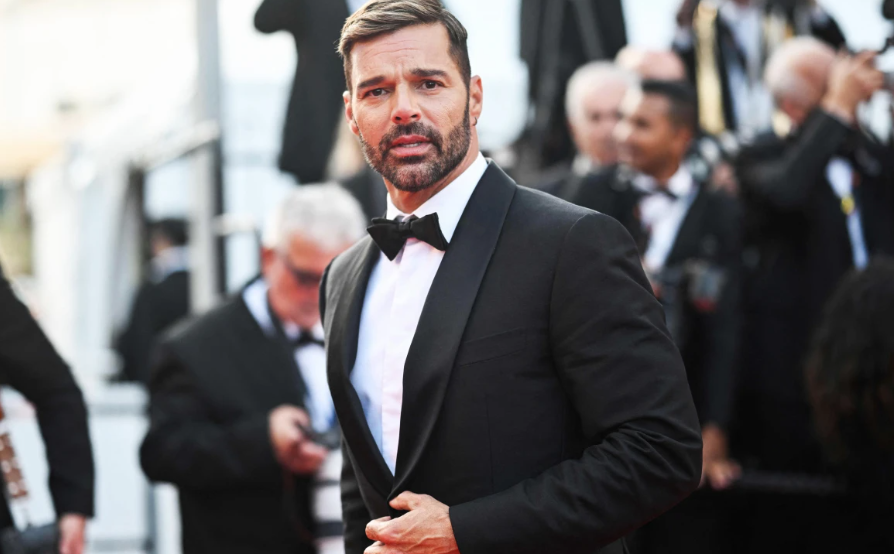

Mexico, which has a long history of pedophilia, was the scene of another of the most mediatic scandals, the one that starred Father Marcial Maciel (1920-2018), founder of the Legionaries of Christ, one of the most widespread, rich, and world influencers

Since then, and according to data from the Mexican Episcopate Conference (CEM), at least 271 priests have been investigated for sexual abuse “without finding consequences,” explains Cristina Sada Salinas, a social activist against clerical abuses in the northern and conservative state. from Nuevo Leon.

Maciel was accused of sexual abuse by dozens of seminarians, a complaint that opened the door for singer Ana Lucía Salazar to reveal in 2019 that she had also suffered abuse between 1991 and 1993 at a Legionnaires’ school in Cancun.

“What they did was what they always do, they took (the accused cleric) from Cancun. Overnight he was gone,” explains Bani López, who also denounced the same school and whose only wish is that the Legionaries disappear.

“For every victim, we know of, there are probably 50 or 100 more,” insists Sada Salinas, for whom reparation can never come without acknowledging the serious situation within multiple religious institutions in Mexico, a deeply believing country.

“Hopefully one day the Church will become a refuge for victims and not a refuge for abusers as it is today. And in this way, we would-be allies,” Chilean Murillo underlines with a glimmer of hope amid so much pessimism.