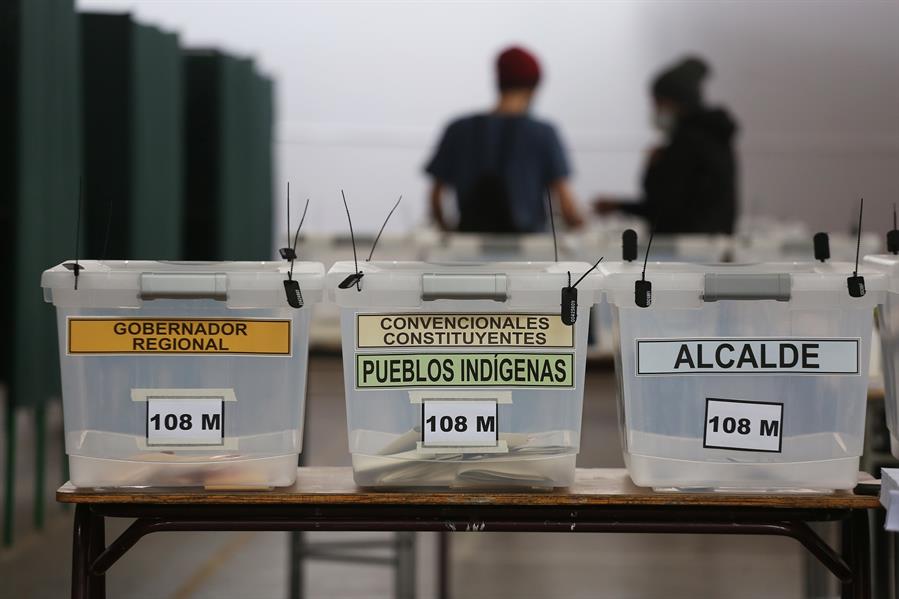

In the last year and a half, Chileans have been summoned to the polls not infrequently: a plebiscite for a new Magna Carta, constituent elections, a municipal vote, and the first regional elections in their history.

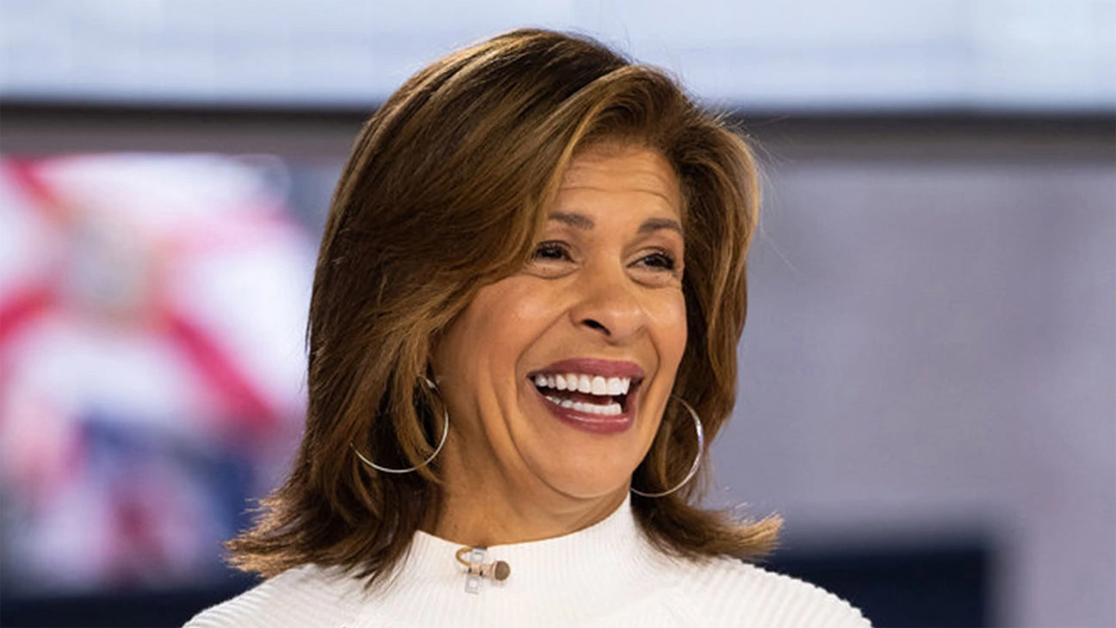

But this November 21, in which the new president who will relieve the conservative Sebastián Piñera for a period of four years will be elected in the first round, the climate is different.

With the extreme right on the rise, the drafting of a new Constitution underway, pressing inflation after the pandemic, and a strong social and institutional crisis that has not ceased since 2019, experts agree: Chile faces the most crucial elections in its recent history.

WHAT IS VOTED

The main event is the election in the first round of the new president, although Parliament will also be renewed, with the election of all the deputies (155) for a period of 4 years and the vote of 27 of the 43 senators for a period of 8 years.

Although there is mistrust towards the polls due to their mistakes in the last votes, almost all agree that none of the seven candidates would win in the first round, in which almost 15 million people are called to vote.

If the predictions of the main polls are fulfilled, which have not been correct since 2019, Gabriel Boric, of the Broad Front (left), and the far-right José Antonio Kast, of the Republican Party, would go on to vote on December 19.

TRADITIONAL PARTIES IN CHECK

It is in doubt that Yasna Provost (New Social Pact, center-left) or Sebastián Sichel (Chile Podemos Más, moderate right), the letters of the two large blocks that shared power since the departure of the dictator Augusto Pinochet ( 1990).

It would be the first time that the two contenders in the second round are not part of these two great coalitions, known during the dawn of the transition to democracy as “Concertación” and “Alianza”.

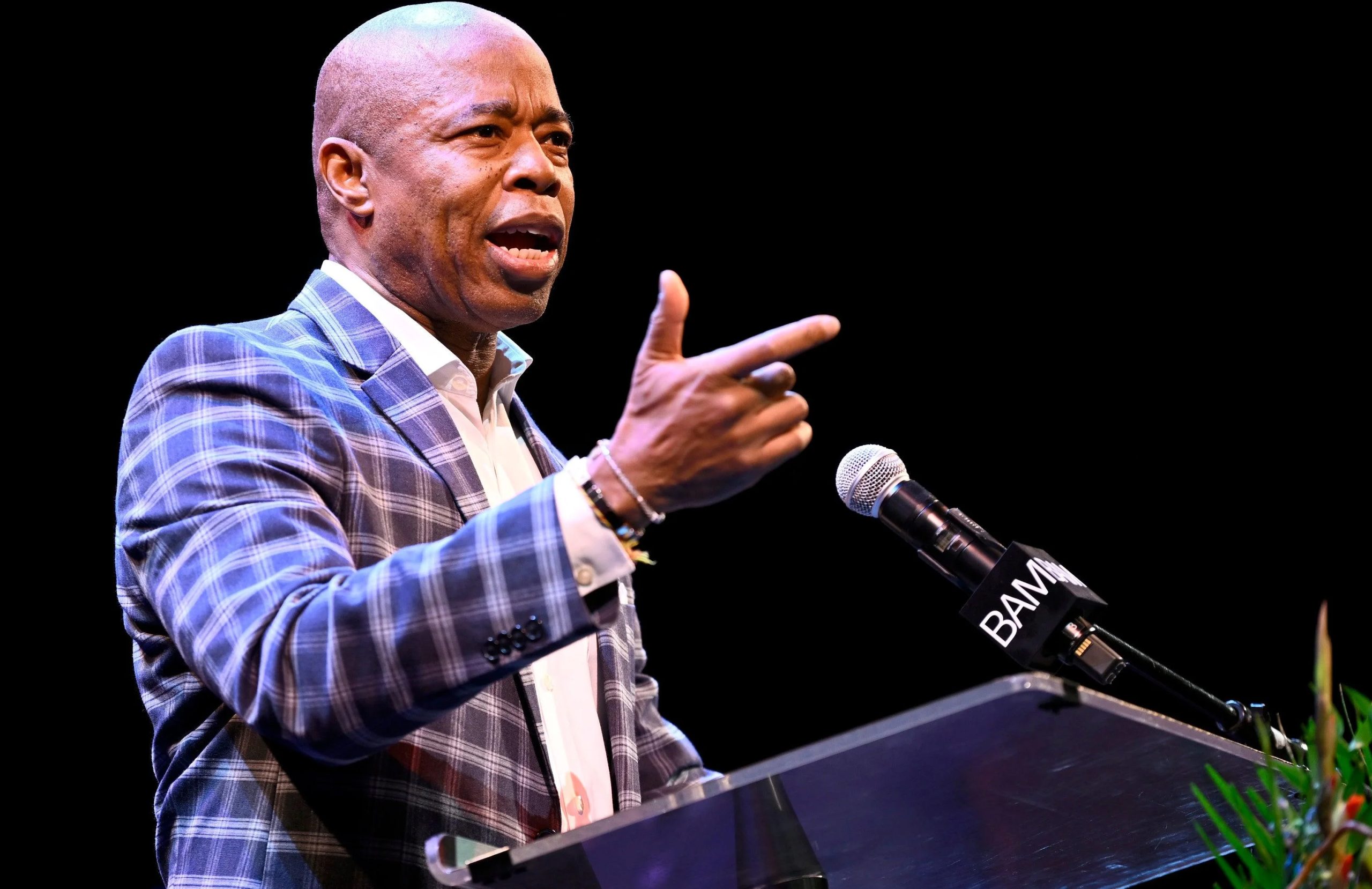

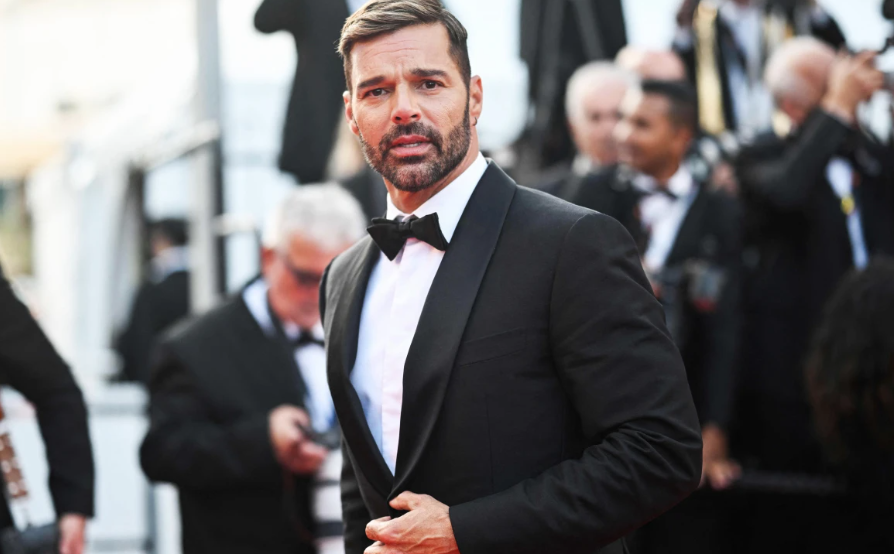

Other candidates with less adherence are the progressive Marco Enríquez-Ominami, the ultra-left Eduardo Artés, and Franco Parisi, a controversial economist who resides in the United States and who will not be in the elections because he has covid-19.

RISE OF THE ULTRA RIGHT

In an unprecedented way in 31 years, a far-right candidate has the potential to reach La Moneda, the presidential seat. This is Kast, an ultra-conservative with a harsh anti-immigration discourse who has managed to double his support in the last two months to over 20%.

The South American country thus joins the hardest conservatism boom that has emerged in recent years in the United States, Brazil, Spain, Hungary, or France.

Digging a ditch to prevent growing irregular migration or his strong discourse of “order and combat violence” in the south, where this year a fierce conflict between indigenous people and forestry companies has worsened with shootings and fatalities, are some of his proposals and the key to its success, according to experts.

The decline of Sichel, a candidate of the ruling right and former minister of the current president and much questioned among conservatives for his centrist position and various controversies that dotted his campaign, would also have to do with his rise.

THE MAIN CHALLENGES

Since October 2019, when the sound of “Chile woke up” a wave of protests unparalleled in its 31 years of democracy was unleashed, the country is mired in a strong social and institutional crisis.

These revolts, in which some thirty people died and thousands were injured, but the current government and the security forces in check and served to initiate a constituent process led by an assembly with a progressive tendency.

The implementation of the new fundamental law and citizen discontent, which is still present through minority demonstrations, are some of the thorniest tasks of the new head of government.

The other great challenge: post-pandemic economic recovery. The South American country faces an escalation of inflation (accumulates a rise of 5.8% so far this year), which has pushed the Central Bank to take unprecedented measures in more than 20 years.

Citizens rush the last state aid before the end of the year and take advantage of the consecutive withdrawals of approved pension funds to face the crisis, while experts look suspiciously at Chile’s financial system, which in the last three decades has been one of the most stable in the region.