His mission today, he explained in his speech, remains to speak for the millions of innocents murdered by the Nazi regime. He expressed his concern that the Holocaust and the extermination are “increasingly forgotten”

Before the European Parliament, Margot Friedländer wears an amber necklace around her neck, from which she never separates. It was the last memory of her that her mother left her after being transported to Auschwitz, along with an address book and a message: “Try to make your life.”

At her 100th birthday in November, Friedländer can say that she has achieved it: she is the living memory of the horror of the Holocaust, but also of a legacy dedicated to telling how, when she was barely in her twenties, she survived the Theresienstadt concentration camp and, already close to his ninety years and after a life in the United States, he decided to return to Berlin to fulfill a mission: to ensure that no one forgets what happened.

Coinciding with the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust, the European Parliament joined this Thursday the long list of public places in which Friedländer has told the world his testimony and his warning that “it can happen again”.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/C7EYBMDIKUIJ6J7WVHNJMNS7DI.jpg%20420w) Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander reacts after being applauded by members of parliament during a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves Herman

Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander reacts after being applauded by members of parliament during a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves Herman“In many countries, no one lifted a finger to save their Jewish neighbors from deportation,” he recalled before the European Parliament. His brother, Friedländer narrated, was arrested when he was still a minor and his mother did not hesitate to surrender to the Gestapo to “accompany him wherever they took him.”

When Margot arrived home to find it empty, her neighbors could only tell her what had happened and give her the last of her mother’s belongings.

At the age of 21, she was left alone in Berlin and spent fifteen months hiding in different friends’ houses before being arrested and deported to Theresienstadt, in the territory of the Czech Republic. In this concentration camp, where he slept on a wooden bed and without hygiene infrastructure, he saw many of his companions die of hunger or disease, punished by the harsh Central European winter.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/TD2S637E7BE7RPOCJSHDF4XYOQ.jpg%20420w) Theresienstadt concentration camp

Theresienstadt concentration campStill a prisoner, she met again with Adolf, a young Berliner whom she knew from her life before the Holocaust, with whom she had secret meetings during the months in Theresienstadt and married just a few weeks after the liberation of the camp in May 1945.

“At first,” she revealed, “I wasn’t in love with him.” “She needed time to be a person again, to have feelings again. Maybe it was the pain that brought us together, more than being in love. We wanted a normal life.”

He gave her his father’s wedding ring, one of the few objects that were not taken from them in the camp, and a rabbi married them on June 30, 1945, 53 days after the “unreal” moment of leaving Theresienstadt free.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/6L3X3ZLDV4A3UABYBXZDGZHETU.jpg%20420w) Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander reacts after being applauded by members of parliament during a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves Herman

Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander reacts after being applauded by members of parliament during a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves HermanThe couple moved a year later to New York, where Adolf’s sister lived and where Margot stayed for 64 years. From their arrival in the United States and until Adolf’s death in 1997, the couple traveled extensively to Europe, but never to Berlin, where he refused to return.

Without her husband, in 2003 – almost 60 years after being deported – Margot returned to “her Berlin” for the first time. In 2010, at the age of 88, he made the final move and settled back in Germany.

“I came back with a message that I have been transmitting ever since: asking people to become contemporary witnesses,” Friedländer explained. “What happened has already happened, we can’t change it, but it can’t happen again.”

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/JWZGEKBZJH3CQJOB732SZ3RHRU.jpg%20420w) Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander attends a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves Herman

Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander attends a special plenary session to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium January 27, 2022. REUTERS/Yves HermanHis mission today, he said, remains to speak up for the millions of innocents murdered by the Nazi regime. He is concerned that the Holocaust and extermination are being “increasingly forgotten” and “abused.”

“I can’t believe it when I see in my hundred years how the symbols of our exclusion by the Nazis are used shamelessly by the enemies of democracy in the street, to paint themselves as victims,” Friedländer lamented, referring to the use of the stars of David by, among others, anti-vaccine groups.

”We must stay together so that the memory of the Holocaust lives on and is not abused by anyone. Hate, racism, and discrimination cannot have the last word”, he asked the European Parliament, from which he received a very long hug and the emotion of many of the deputies present.

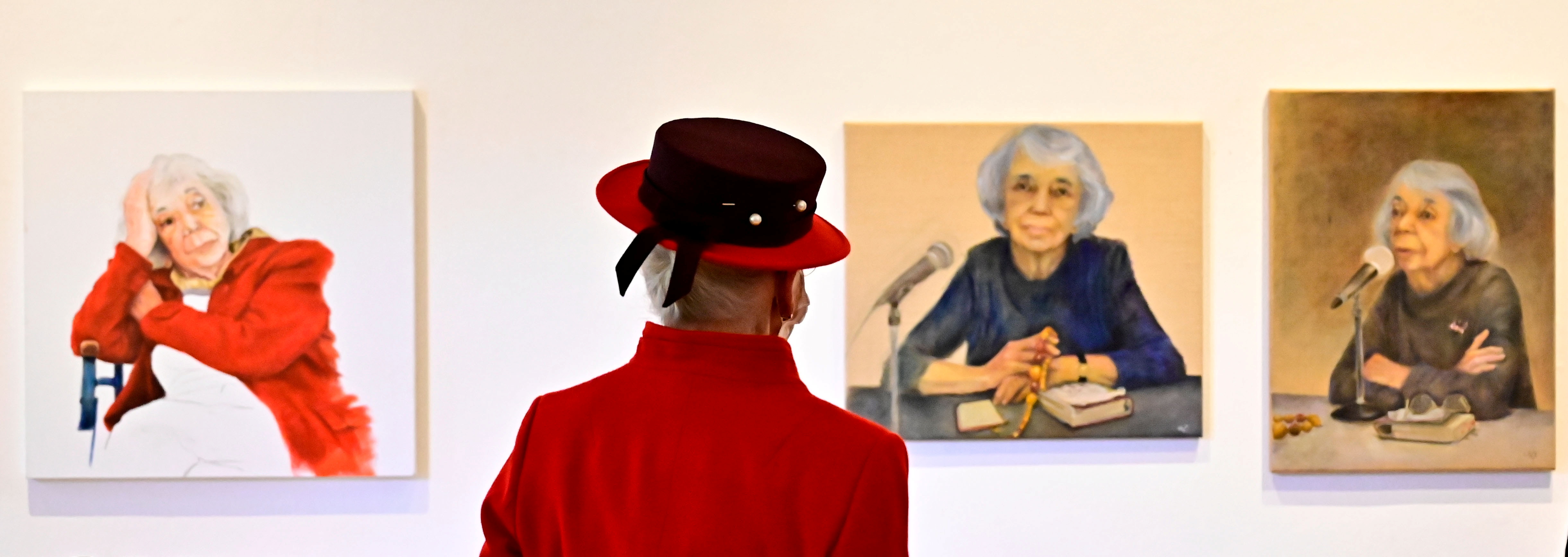

Queen Margrethe of Denmark looks at portraits of German Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander as she visits the Literaturhaus (house of literature) in Berlin, Germany. Tobias Schwarz/Pool via REUTERS

Queen Margrethe of Denmark looks at portraits of German Holocaust survivor Margot Friedlander as she visits the Literaturhaus (house of literature) in Berlin, Germany. Tobias Schwarz/Pool via REUTERSAfter her, the leaders of the community institutions spoke briefly, such as the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, who asked Europeans to be “custodians of this memory” and take responsibility for transmitting the message of the survivors when they can no longer do so.

“The horrors of Auschwitz are unspeakable, but we must tell them,” summed up the President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, for whom Europe today is a “political manifestation of ‘never again’.”

”Sharing these memories”, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told Friedländer, “is the greatest act of love for all of us and future generations, because it makes us see, it makes us free. Our freedom is built on the memory of the Holocaust.”