A century ago the name of the teenager Leonard Thompson entered the history of diabetes treatment. Seriously ill, he received an injected dose of insulin in a Canadian hospital, a puncture that would mean the difference between life and death.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in the world 422 million people live with diabetes, a disease that a hundred years ago meant certain death and that today can be treated thanks to insulin.

The discovery of a technology to purify insulin and inject it into people was “a matter of life and death for patients” because diabetes mellitus or type 1 begins when you are still very young and a century ago it meant death.

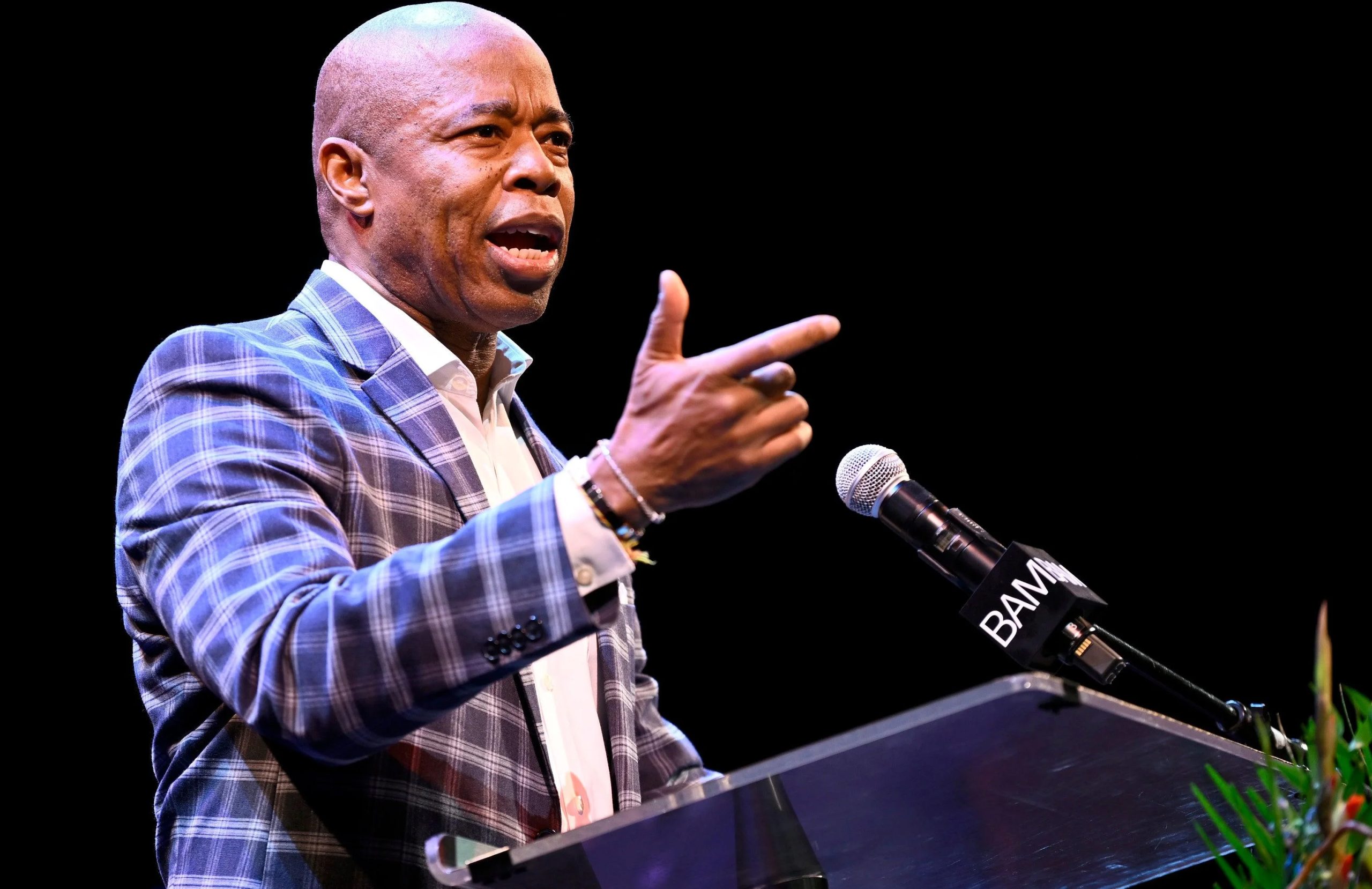

This is stated by the researcher of the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) German Perdomo, of the Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics of Valladolid (central Spain), who addresses the history of this injection and new research in the treatment of diabetes, from the so-called artificial pancreas to stem cell testing.

On January 11, 1922, Thompson was 14 years old, had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus two years earlier, and was in Toronto General Hospital (Canada), on the brink of death, treated with a 400 calorie daily diet and with only 23 kilos of weight.

That day he received the first injection, but “it was not very successful,” says Perdomo. Although urine glucose levels dropped somewhat, treatment was discontinued due to an allergic reaction to the used dog pancreas extract, which was not yet sufficiently purified.

However, the team of researchers at the University of Toronto did not give up. Back at the laboratory, on the 23rd he was subjected to a second prick with a new extract.

There was a clinical improvement, his glycemic index dropped and he began to regain mobility, making Thompson the first patient to be successfully treated. A few weeks later another six underwent the same treatment.

Getting to that moment was the fruit of many years of work. Since the end of the 19th century, some researchers pointed, in tests with dogs, to some substance in the pancreas as the key to regulating glucose levels and in the first years of the 20th, tests were carried out to treat patients with a pancreatic extract from animals.

A key figure in the discovery of insulin was the young Canadian researcher Frederick Grant Banting, who in 1921 proposed the University of Toronto Professor of Physiology John Macleod to investigate with the help of his assistant Charles Best.

Banting would be the author of the first pancreatic extract that was administered to the adolescent on January 11, 1922, and on the 23rd the test was repeated, on that occasion with another carried out by the biochemist James Collip, who “put the talent to purify it,” he says. Perdomo.

The discovery of insulin would earn Banting and Macleod the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1923, an award not without controversy for the team’s disagreements over the attribution of merit. Other scientists, such as the Romanian Nicolae Constantin Paulescu or the German Georg Zuelzer also raised objections.

The first injection in a human was made, “without much success”, by Zieler, who worked in the United States, and was the first to file a patent on insulin. Paulescu was “the great forgotten ones,” adds the CSIC researcher, as he had reached the same conclusions as Banting before but the First World War forced him to suspend his investigations.

The 20th century was marked by advances. The first move on to using cow pancreas and further refining the purification process. Protamine insulin was created in 1936 to reduce the number of punctures to one or two a day.

In 1958, Frederick Sanger received the Nobel for determining the chemical sequence of insulin, and in 1977 the award went to Rosalyn Yalow, “for a spectacular advance” – says Perdomo – in measuring insulin in the blood. Soon after, recombinant human insulin was achieved, which prevents rejection from the body.

Rapidly absorbed insulin, “which gives more tools to manage patients” and the first generation of long-acting synthetic insulin (2000) and the second generation are other highlights, according to the researcher.

The invention in 1981 of the first insulin minipump and later the first sensors led, already in this century, to the development of what is called the artificial pancreas.

It is “a substantial advance for the patient,” according to Perdomo, as it combines a glucose sensor and a minipump controlled by a computer algorithm, which continuously monitors glucose levels and when they rise, injects the necessary amount of insulin.

Currently, research is putting emphasis on the artificial pancreas to “improve existing technology, make algorithms more powerful and more efficient.”

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks the pancreas, preventing the body from making insulin, a disease that usually comes on early.

Today we are working on identifying people at risk, looking for biological markers, “that tells us with high reliability” that possibility, and treating them with drugs to prevent their onset.

Perdomo also points out the importance of stem cell research to try to regenerate and equip the body with the cells that the disease destroys in the pancreas and for the patient to be able to produce their own insulin.