Britta Foster and Minerva Tiznado are in different leagues when it comes to healthcare. Foster, who married a member of the family that owns the $ 2.5 billion Foster Farms poultry business, has Blue Shield coverage as well as a high-end primary care plan that gives you 24/7 digital access to your doctor. / 7, for an annual fee of $ 5,900 that also covers her husband and two of her children.

Tiznado is from Nayarit, Mexico, and does not have insurance. It has free primary care visits and deep discounts on medications, lab tests, and imaging.

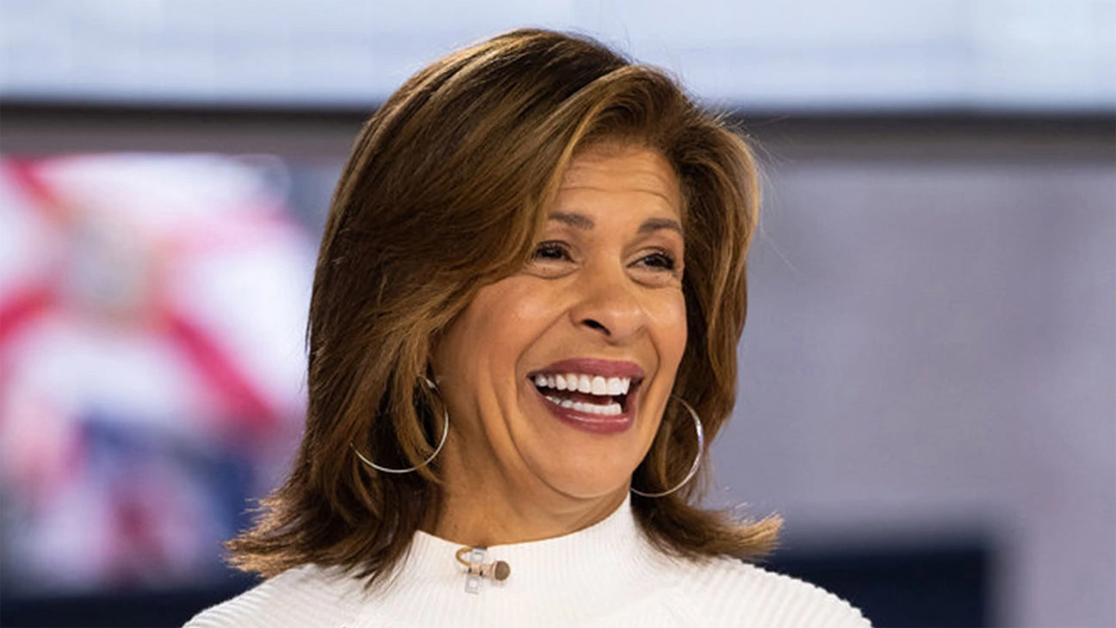

But Tiznado, 32, and Foster, 48, receive medical care at the same place: Lukes Family Practice, in this Central Valley city of about 217,000 people.

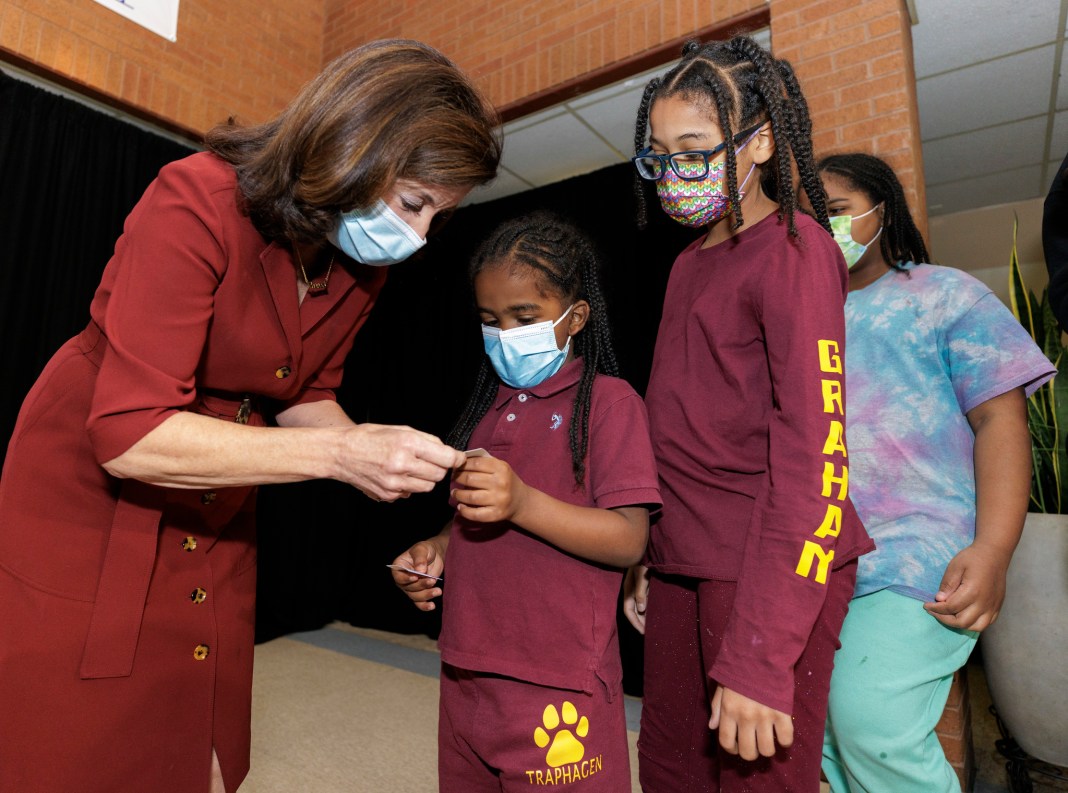

Lukes, a four-person clinic located in a nondescript shopping mall, offers an unorthodox combination of bespoke medicine for the wealthiest and charity care for the uninsured.

The annual fees that St. Lukes collects from Foster’s family and 550 other paying patients help cover free care for a somewhat larger number of uninsured patients, many of them, like Tiznado, Spanish-speaking immigrants who cannot obtain Medicaid for not having documents.

The clinic does not accept any type of insurance but requires paying patients to have coverage for medical expenses outside of their scope of care.

These patients, whom St. Lukes calls benefactors, say they are happy to participate in this Robin Hood model. It provides them with highly personalized care with great access to their doctors and the emotional satisfaction of supporting the underprivileged, the beneficiaries.

Foster said it has been a huge benefit for his family to be able to text or call his doctor at any time and be seen in no time:

Knowing that your group is here to serve our community, too, makes it all seem even more important.

Tiznado, who came to the clinic one morning in September for a scheduled ovarian cyst checkup, said that St Lukes has helped us a lot, financially and in every way.

I think if we moved to another place, I would keep coming here. But Tiznado and the other uninsured patients don’t have the same 24/7 access as benefactors. The two groups used separate waiting rooms until the pandemic hit.

Lukes is a local response to systemic problems in American healthcare, such as physician burnout, patient dissatisfaction and the fact that millions of people continue to lack care.

Nearly 3.2 million Californians, including 1.3 million undocumented immigrants, will be uninsured in 2022, although the state is gradually expanding Medicaid coverage to many immigrants. Lukes is part of the movement for direct primary care, an alternative for doctors fleeing insurance-dominated medical groups.

About 200 direct primary care practices open in the United States each year, and there are currently 1,581 employing about 3,000 physicians, according to Dr. Philip Eskew, founder of DPC Frontier, which offers resources to physicians who want to make the change.

This is a small portion of the nearly 209,000 primary care physicians in the United States.

It is true that we are a small movement at the moment, Eskew noted.

Its biggest challenges are regulatory. For example, if clinics accept fees from people who are enrolled in Medicare, their doctors must waive Medicare reimbursement wherever they practice. In addition, some state regulatory bodies may consider direct primary care practices as health plans and impose conditions or restrictions that make it difficult or impossible for them to function.

Direct primary care physicians often charge patients a monthly or annual fee in exchange for increased phone, text, or video access, shorter wait times, and longer face-to-face visits.

And they generally don’t accept insurance, eliminating the need to chase after bills and treatment authorizations.

At my old practice, we spent almost half of our time processing collections. I thought that if we could get rid of all those expenses, we could spend more time with patients, and it turned out to be true, said Dr. Bob Forester, creator of the concept and co-founder of St. Luke’s.

Investor-owned high-tech companies such as One Medical or forwarding Health are frowned upon by many direct primary care physicians. They are seen as direct primary care businesses, but critics say they are more focused on expanding volume than offering personalized service.

Direct primary care is one in which the doctor has a relationship with the patient. We don’t have to be accountable to an investor, because our investors are our patients, explained Dr. Maryal Concepción, a family doctor in Arnold, a small town in the mountains of California, who recently left a business consultation to start her business. own direct primary care consultation.

St. Lukes paying patients must have insurance that covers hospitalization, surgeries, specialty care, imaging, and prescription drugs.

The clinic usually gets big discounts for its uninsured patients. For example, Quest Diagnostics charges them just 10-15% of their regular price for lab tests, said Dr. RJ Heck, one of the two St. Lukes family doctors and a co-founder of the clinic. Uninsured patients in need of operations are often referred to Surgery Without Borders, a Bakersfield surgical center with reduced fees.

St. Lukes recently received a $ 75,000 grant for imaging, lab tests, X-rays, and some medications from the Legacy Health Endowment, a local foundation. And he works with several radiology groups that offer discounts, Heck added.

Tiznado, who needs regular ultrasounds for his ovarian cysts, explained that he pays about $ 150 for them. If I did it elsewhere, it would cost me between $ 900 and $ 1,200, he said.

St. Lukes’ tax-exempt nonprofit status encourages donations, including from local benefactors such as Foster Farms and wine producer E. & J. Gallo. Some workers at donating companies are among St. Luke’s uninsured patients.

The tax exemption also confers a benefit on paying patients: They can deduct from their taxes the part of their annual premiums that they do not use for health care. St. Lukes sends them a statement each year assigning a dollar value, based on Medicare prices, of the services they have received.

Forester said St. Lukes’s grew out of his concern for the uninsured and his disregard for bureaucratic systems. But the bottom line, he said, is that the idea for St. Lukes was born in an inspired moment of prayer. Forester and Heck started it more than 17 years ago as a Catholic-inspired medical practice.

However, although Catholic symbols adorn the walls of St. Lukes, many of his patients are not Christian, and Catholic medical doctrine is not central to their practice.

Nobody comes here to control or tell us what we should or should not do, said Dr. Erin Kiesel, the other family doctor at the clinic.

Kiesel said that she would not prescribe an abortion, but that she would tell someone where to go if asked, which no one has done. Heck and Kiesel took big pay cuts to come to St.

Luke’s. Kiesel makes about $ 60,000 less a year than in her previous visit. For her, having more time with patients, less paperwork, and a better work-life balance more than compensates for the lower salary.

Patients cited the personal relationships they have established with their St. Luke’s providers. Paul Neumann, a 25-year patient of Heck’s who followed him to St. Lukes, said that relationship was a godsend.

He said that in 2009 he returned from a trip to Rome with pneumonia. When his wife called Heck the next morning, he immediately came to the house.

Neumann, 84, pays St. Luke’s more than $ 10,000 a year for himself, his wife, and their son’s family.