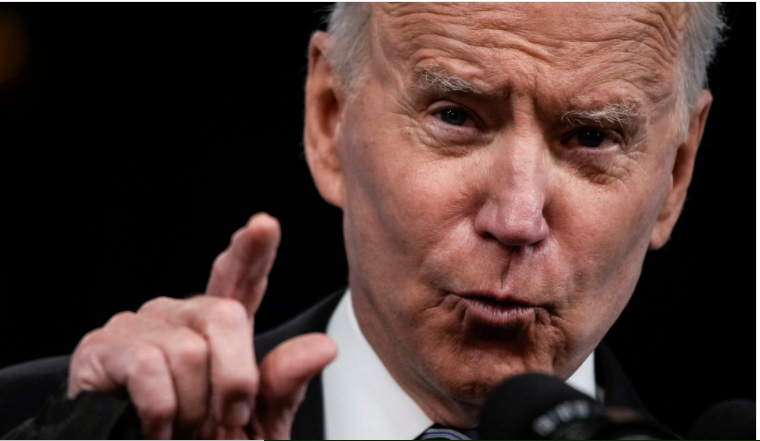

(CNN) – Joe Biden’s presidency and top Democrats are suddenly faced with a moment of truth with a bold nation-change agenda that is threatened by the treacherous political math of divided Washington and tough resistance from Republicans. pro-Trump.

Now a crucial phase is unfolding with President Joe Biden’s plans to redefine the concept of infrastructure, with massive government social spending, held back by shaky bipartisan talks with the Republican Party. Hopes for a radical voting reform law to counter Republican efforts in the states to restrict access to the ballot have no clear path to follow in the Senate.

A bipartisan campaign for a relatively modest tightening of background checks for some gun buyers runs the risk of failing. The best chance for a headline-grabbing victory may be the intense talks on police reform between Republican Sen. Tim Scott and two top Democrats. But hopes that a deal could be reached before the anniversary of George Floyd’s death this week have been dashed. And the president has yet to reveal planned efforts to address immigration reform and climate change, two highly divisive policy areas.

Biden is trying to capitalize on the perception among Democrats that after a pandemic only in a century and a severe economic crisis, the country is ready for a fundamental shift in attitude toward ambitious government solutions.

But the reality of a 50-50 Senate means that you can’t even guarantee that your entire own party is on the side of your bigger goals.

Republicans, still slaves to former President Donald Trump, have already headed for war toward the 2022 midterm elections. This week in the Senate, they are expected to block an independent bipartisan commission investigating the insurrection on the US Capitol. January 6th. The move would further enshrine the turnaround of a party that once boasted of winning the Cold War against totalitarian communism away from safeguarding democracy in its own country.

Perceptions of the economy – always a major driver of political sentiment and key to a president’s authority – are caught in a strange limbo. Some signs point to a rebound to coincide with the roaring twenties 100 years ago, but other data on employment and inflation provide an opportunity for GOP claims that Biden’s big government policies are causing trouble.

A critical moment

During his first 100 days in office and in a largely successful attempt to scale the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines he inherited from Trump, Biden was able to tap into a tide of public support based on the fact that at last a President was taking the pandemic seriously. However, now that he sets out to implement a partisan agenda, his political task becomes much more complicated. The nature of a presidency born out of crisis is to undergo successive tests of authority and political prowess. And Biden is about to face another.

The president has made the effort to find common ground on infrastructure reform the litmus test of his promise to unite the country, which anchored his 2020 campaign and is a centerpiece of his entire presidency.

That belief in bipartisanship was made clear last week when the president signed into law a bill protecting Asian and Pacific Islander Americans from a rising tide of hate-motivated attacks, which largely garnered support in the hall despite 62 Republicans in the House of Representatives and one in the Senate oppose it.

“I am proud of the United States today. I am proud today of our political system, of the United States Congress. I am proud today that Democrats and Republicans have stood up together to say something, ”said the president.

Biden, however, may be the only person in Washington with so much faith in a system burned down by the bitterest partisanship, Trump’s attacks on democratic norms and a fundamental disconnect in the purpose of government. Some Democrats believe the president is wasting time negotiating with Republicans who believe they will never offer a counterproposal that comes close to progressive hopes.

Still, Biden’s faith, or desire at least to show voters that he hasn’t given up on the aspirations that funded his appeal to more moderate voters, led him to take a key role in conversations with a small group of Republican senators who started with encouraging noises, but it seems that it is sinking into the insurmountable divide between the parties. If the president’s attempt at a bipartisan infrastructure deal fails, it’s hard to see any other problem where his vision of unity has any chance of being realized.

Republicans oppose both Biden’s broad infrastructure vision, which includes significant social spending, and partially reducing Trump’s corporate tax cuts to pay for it.

But the White House insists that cutting the package from $ 2.2 trillion to $ 1.7 trillion is a good faith offer to keep the Republican Party on board. There is a palpable sense in Washington that the defining moment of the plan is approaching.

“[Biden] will not allow inaction to be the answer. And when it gets to the point where that seems inevitable, you’ll see it change course, “said Cedric Richmond, a senior White House adviser, on CNN’s” State of the Union. ”

The problem for Biden is that a move to go it alone, to try to pass a bill based on Democratic votes with intricate parliamentary maneuvering in the Senate, could pierce the aura of unity and centrism with which he has disguised his presidency and was important. for the approval of its covid-19 rescue bill.

Still, assuming the president can solve the puzzle of how to get moderate Democrats like West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin to support the bill, he could get the credit of voters for tackling the obstruction of the Republican Party. if any subsequent partisan infrastructure plan ends up being widely publicized.

Biden’s relationship with progressives is about to be tested in a big way

The president must become increasingly concerned about his left flank, as well as the deteriorating hopes of infrastructure talks with Republicans on his right.

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who chairs the Senate Budget Committee, sent a clear signal of progressives’ growing impatience with bipartisan efforts that many of them feel do not enjoy bona fide partners.

“We would like to have bipartisanship,” Sanders said on CBS’s “Face the Nation.”

“But I don’t think we have any seriousness on the part of the Republican leadership to address the major crises facing this country, and if they don’t move forward, we have to move forward alone,” said Sanders, whose praise of Biden’s covid-19 aid package provided coverage for the president with the Liberals earlier this year.

But ties between progressives and Biden have been further strained by the president’s behind-the-scenes role in mediating fighting between Israel and Hamas last week as Palestinian casualties mounted.

Progressives are feeling that the president, despite embarking on a liberal economic agenda, is not firmly in his corner at all.

Biden recently told The New York Times columnist David Brooks that the United States had no choice but to “go big” in the face of challenges to its competitiveness and power from nations like China. But he also seemed to indicate that his vision of expansive political change was not necessarily aligned with the perceptions of many in his own party.

“Progressives don’t like me because I’m not ready to assume what I would say and they would say it is a socialist agenda,” Biden said.

Such a worldview could help explain why Biden is eager to expand the social safety net with policies that help American workers and tilt the balance of the economy toward the less well-off, but is reluctant to accept the expansion of the Supreme Court or end Senate obstructionism.

The next few weeks will begin to define exactly whether Biden’s thinking about the political moment offers a path for his preferred path forward or whether he will have no choice but to turn to a more partisan approach to maximize what may be a narrow window to get things done. as the midterm elections loom.